Ballast organisms are small aquatic creatures who live in the water used by shipping vessels for hydrodynamic stabilisation. When a ship offloads cargo in a port, it can become it top-heavy: ballast water is collected in its hull to offset this. The ship then travels on to the next port where it collects new cargo, so the ballast water is now discharged. This water, taken up from coastal areas, is often teeming with small, aquatic creatures – ballast organisms, an international population of critters cutting laps of trade routes.

3-5 billion tonnes of ballast water is transferred throughout the world each year, and the amount is increasing. Ballast creatures are starting to turn up in new places as new shipping routes open up and oceans warm, like the Northwest Passage in the Arctic Circle. They don’t necessarily establish a new life for themselves upon discharge though – many simply die due to the different climate – or get sad and don’t want to procreate. To be a successful ballast organism you need to be wearing the proverbial look that adapts from the trail, to the club, to meeting the parents.

“It’s barnacles first, then sponges, then mussels, then crabs, then fish,” a sailor in Fremantle tells me. “Barnacles are cosmopolitan, they’re everywhere. They have the longest penises in relation to their body size out of any animal.”

Divers and fishermen, two classic genres of citizen scientist, often end up in a position of expertise on ballast organisms. Dan Monceaux, one such field researcher from South Australia, has authored papers on the “menagerie of organisms hitchhiking around the world.”

“A bivalve that was extinct in South Australia decades ago has been reintroduced from the east coast via shipping. South Australian ports have several gas-fired power stations, and one of their influences is hot water discharge, or thermal pollution, leading to a species of upside-down jellyfish from Tonga managing to live near the power plant. The only explanation for it is ballast water. The whole harbour of Port Adelaide is swarming with introduced species. The inner harbour where the water is flushing the slowest, it’s a teeming cesspool of exotics. Not quite monocultures but not biodiverse. You have corridors or mats of exotic species that have just taken over.

“The state biosecurity response is pretty fascinating – generally they don’t really care unless it can have commercial ramifications – say a sardine is transported here from South America and brings with it a pathogen that can transfer to local fishes who have no immunity for it. Anything else doesn’t matter. Ballast organisms are handled as a primary industries matter, not an environmental matter.”

“Giant African Snails are the size of a pint,” another Freo sailor says. “Salt is poured around a shipping container to quarantine it if it looks like it’s got snails.”

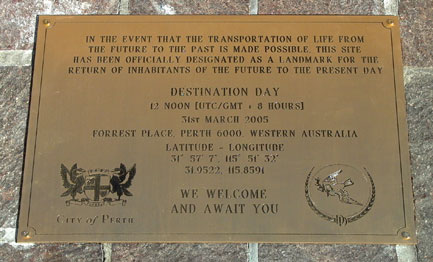

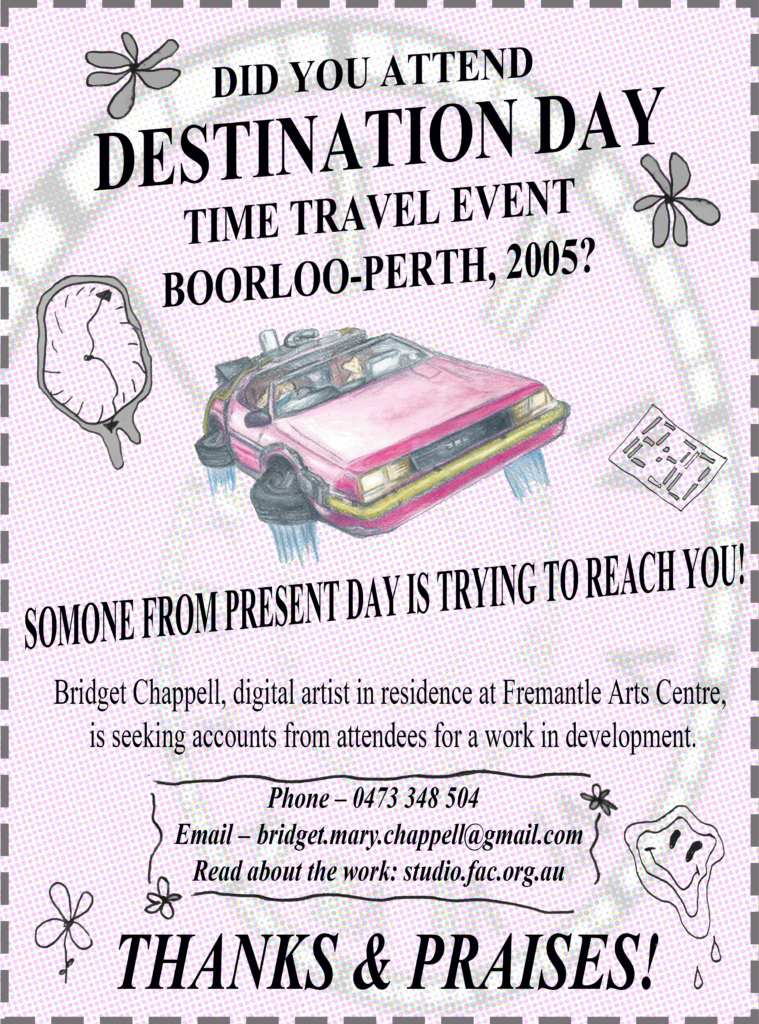

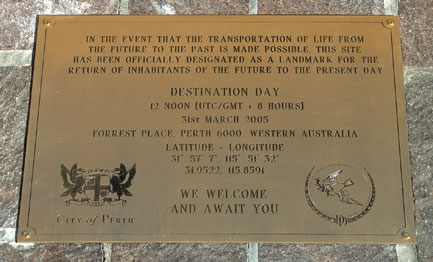

On 31 March, 2005, a gathering for time travellers was held in Forrest Place in the CBD of Perth. “Destination Day” welcomed time travellers from the future to gather with revellers of the present. The hope was to commune with brethren from whatever century, and learn about the technology that had allowed them to “return” to present day.

No attendees from the future revealed themselves, though from scant documentation available online the party looked pretty good regardless. One of the more curious aspects is Perth city council’s official support for it, both in provision of the town square and the commissioning of a bronze plaque announcing the event. This plaque was presumably intended as the permanent Destination Day invitation for future generations.

The plaque was made by sculptor Christian de Vietri (who has so far been unavailable for comment). The City of Perth’s current public art officer, Odd Anderson, informed me in email correspondence that the plaque has in fact now been removed, and is no longer in the City’s possession. The removal is a significant one: in so doing, Destination Day’s offer extended to the future at large was retracted by a bureaucratic third party, scuttling any chance of participants of various times converging. It’s unconfirmed when the plaque was removed, but it means the people of Perth had a maximum of 18 years to invent backwards time travel in order to attend the party.

To what end, City of Perth?

Did you attend Destination Day? Have you worked for the City of Perth and know of its inner workings? Can you help? Please, spread the word!

“In civilisations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.” — Foucault

Some have argued that because we haven’t knowingly met time travellers from the future in the present, it means they probably don’t exist. Carl Sagan has suggested their appearance could be more veiled, opaque. Some philosophers say future events are “already there”, like places on a map we haven’t yet visited.

Physicists Gunter Nimtz and Alfons Stahlhofen claimed to have violated Einstein’s theory of relativity by transmitting photons faster than the speed of light. Quantum physicist Aephrain Steinberg used a train analogy to challenge the premise of their experiment: a train travelling dropping off cars at each station between its departure and arrival points means the centre of the train moves forward at each stop.

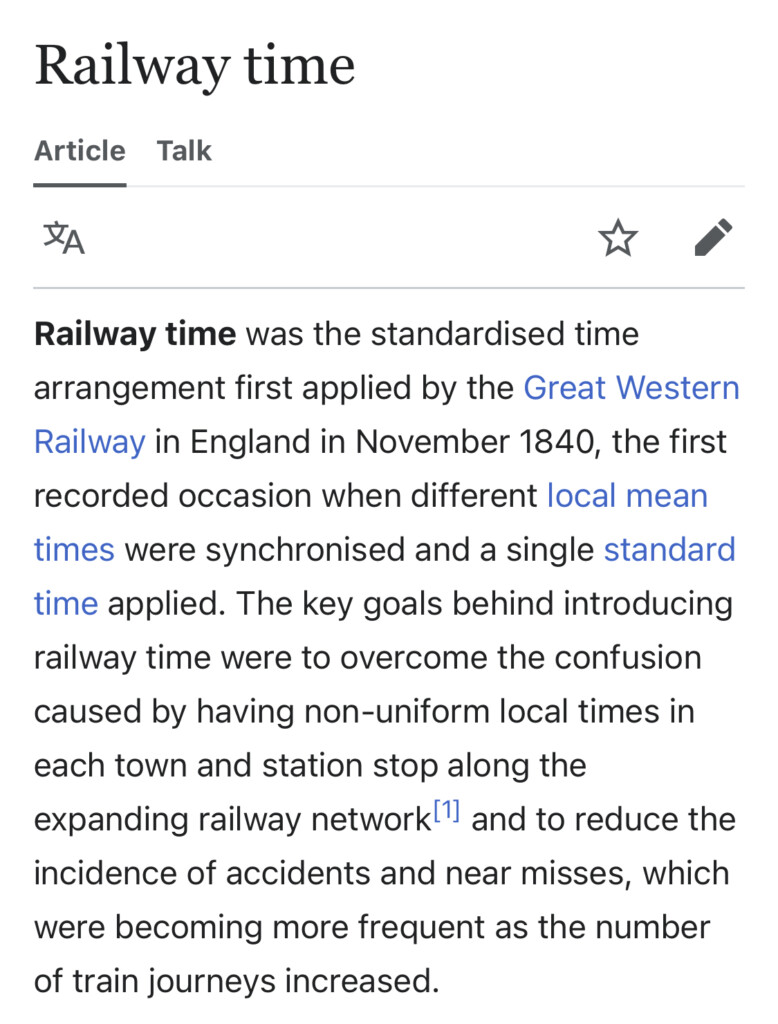

As I spoke about a bit earlier on, modern time zones were invented because of the birth of the railroad, and its unprecedented way of letting you travel cross country very fast – so fast that the sun would now rise and set at different times to a watch you were wearing, and 12 noon on one town’s sundial would be different to that of the next you came to.

The early 2000’s saw a spate of experimental parties hoping to entice people from the future, who have harnessed time travel technology, to come back and reveal their tricks. In 2005, students at MIT held the Time Traveler Convention, and in 2009 Stephen Hawking held a time travellers party that he sent out invitations to only after the fact. Chips and salsa were served at the former; I’m not sure where invites were sent for the latter, but Hawking was the only attendee.

Closer to home, the Boorloo/Perth 2005 “Destination Day”, that curiously was held with the assistance of Perth City Council, invited time travellers to converge at a party at Forrest Place in the CBD. The invitation was extended, somewhat permanently, in bronze, and installed in the pedestrian square. I’ve been trying to learn as much as I can about this event.

If one travels west across the continent by train to Boorloo, there is this kind of non-place, not particularly close to the SA-WA state border, where the time zones change only for trains. I’ve always slept through this part of the journey.

To be continued~

There are several wormholes that occur on train lines. Places where you feel yourself vortex surfing, time and distance grinding to a single halt. Only in some languages are the temporal and physical kept discrete from one another and so struggle to describe the places where trains stop for no known reason and there you’ll stay, you’re pretty sure, forever. That place in the wheat belt, that place in the sugar cane; and that place in the mulga desert.

English makes this distinction, but has no future tense. The much-sensationalised Sapir-Whorf hypothesis says that our mother tongues are not just a way to voice ideas but themselves shape how we perceive the world. For example, if we didn’t have the word “blue” for that colour, naming blue things instead as “having the quality of the sky”, how would your relationship to that colour subtly differ to that of “yellow”, “green”, etc? Or: if you had no inflectional future tense, only “will” or “gonna” to grammatically express what comes next…

Linguistic relativity and its older, harsher cousin linguistic determinism have been long invoked by those lacking even an unfinished linguistics degree (whattup) to make generalisations about other people and their worldviews. I’m a native English speaker and I get what the future is. But I kind of wonder anyway if time travel would come more naturally were I not acculturated to keeping time and place semantically at arm’s length.

L-O-R-E

Phone call with James Hall, sailor and boatbuilder.

Regarding the re-naming of boats

JH: It all comes from old sailing lore, l-o-r-e. It’s bad luck to go out on a boat that still has remnants of a past life. So you appease Davy Jones by removing all the evidence of its past name. It has to be done out of the water, you can burn shit. I’ve done it for dingheys. With the anthropomorphising of boats in general, it all comes down to respect of the ocean. Always being a great unknown and such a large force, that you cannot battle against. And so appeasing the ocean, Davy Jones’ locker, changing the name of something that is gonna be using its space. And that comes down to how boats are always referred to as “she” or “her”, there’s so many different reasons for that, but the one I like the most is how the boat will always take care of you, like a mother’s love. Sailors know the boat will get you home. If you trust the boat, treat it well, have a relationship I guess, um, yeah.

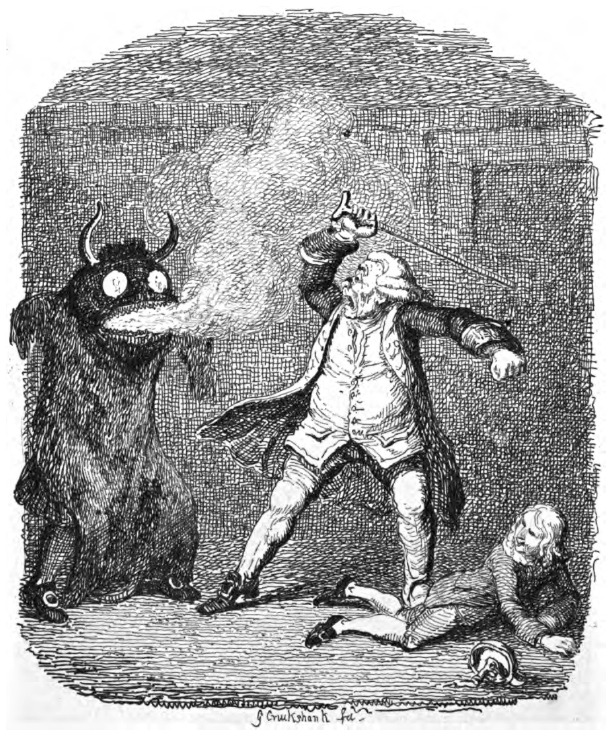

Davy Jones pictured by George Cruikshank in 1832, as described by Tobias Smollett in The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle.

Even more so when you go deep into wooden boats, you can’t “own” a wooden boat, that’s the l-o-r-e around wooden boats. Ownership isn’t a thing, you’re a custodian or caretaker. The soul of the boat and stuff like that, ways and means of repairing boats without taking the soul out of it. There’s sort of a delineation in replacing parts where at what point does it become a new boat. You can change the rig and stuff like that. We had big discussions about it when we bought our boat. One big one that I’m massively against is sheething, where you take a wooden boat and cover it in fibre glass. If you do the work to protect the wood that can carry on being restored and maintained. If you get rot in between the wood and the fibre glass the boat is cooked – that’s the end of the life of the boat.

A boat will grow and evolve itself. The Olive May is the oldest commercial sailing vessel in Australia, started as a trading vessel between Hobart and the Huon Valley. But it changed, and became a fishing vessel. Then they plugged the wet well and made it a passenger vessel. You can see where that’s happened on the outside of the boat. That delineation of what’s old and new on a boat has to be obvious. On that one they used a different planking structure so you can still see where the original lines are. She has a new life now but you can see where it starts and how she adapted to that new life.

In most sailors’ psyches, a boat is something that lives. If you’re out in the middle of fuckin’ nowhere and you get hit by a storm, you can’t do anything by yourself, so in that psychological space the boat has to do something, why else would the boat keep you safe if there wasn’t a mutual respect?

My grandfather sailed to New Zealand in his 30-foot yacht. Him and my auntie went over, her marriage had broken down, her house had burnt down, her dog had just died. She was like, if I die, I die. They copped a really big storm, they saw 80 knots, the weather came outta nowhere. What kept them alive was the boat. They took all the sails down, set a course sort of downwind, doing 8 knots with no sails. Locked the hatch and cooked dinner and went to sleep and the boat did her thing. In situations like that, the humans aren’t controlling the boat in any way, the boat has to have its own sentience. If you see it from a spiritual perspective and whatnot.

People who do long-distance sailing, they quite often end up talking to the boat, as you would. Even from a racing perspective, you have a discussion with the boat. To go faster, you ask, what can we do for her? What can I do as a person to help the boat do the thing? Not force the boat to do a thing. You believe the boat can do it, you’re just there as an aid. It comes from a respect, somewhat, of like, you’re operating in an arena that is bigger than you. You’re operating outside the realms of human activity. You also accept that the captain goes down with the ship, it’s their responsibility to see her through to the end of her life. They are one.

Regarding Hall’s preparation of his own wooden boat

BC: and will you be antifouling it?

JH: Yes.

BC: And how does that work?

JH: Uh… best not to think about it. It’s copper mainly. Chemicals inside a plastic matrix.

BC: Is there internal antifouling as well?

JH: I would say so. The laws around it are pretty hectic. You have to filter it. If you can’t filter it you can’t enter Australian waters.

This week I’ve been reading Paul Virillio’s “The Last Vehicle”, an essay in the dream blunt rotation of Semiotexte’s “Hatred of Capitalism”. It relates to time, movement, agency and spectatorship. If it was a movie I’d like it shown with Guy Debord’s “Society of the Spectacle” and Christopher Lasch’s “Culture of Narcissism”; an all-night horror movie triple feature.

Some highlights:

“Spatial distance collapses suddenly into mere temporal distance. The longest journeys become scarcely more than simple intermissions. – on the beginning of filming cinematic scenes from moving vehicles – cars, trains, etc. … The audiovisual vehicle has triumphed since the 1930s with radio, television, radar, sonar, and emerging electronic optics.

From now on everything will happen without our even moving, without our even having to set out. The initially confined rise of the dynamic, first simply mobile, then automotive, vehicle is quickly followed by the generalised rise of pictures and sounds in the static vehicles of the audiovisual.

If automotive vehicles are today less “riding animals” than frames in the optician’s sense, it is because the self-propelled vehicle is becoming less and less a vector of change in physical location than a means of representation… The more or less distant vision of our travels thereby gradually recedes behind the arrival at the destination, into a general arrival of images… It is thus our common destiny to become film.

If the profundity of time is greater today than that of space, then it means that notions of time have changed considerably. Here, as elsewhere in our daily and banal life, we are passing from the extensive time of history to the intensive time of momentariness without history – with the aid of contemporary technologies. These automotive, audiovisual and informative technologies all operate on the same restriction, the same contraction of duration.

Let us not trust it. It conditions the return to the house’s state of siege, to the cadaver-like inertia of the interactive dwelling, this residential cell that has left the extension of the habitat behind and whose most important piece of the furniture is the seat.”

And from “Culture of Narcissism”:

“Most people, historically, have not lived their lives thinking, “I have only one life to live.” Instead they have lived as if they are living their ancestors’ lives and their offspring’s lives.”

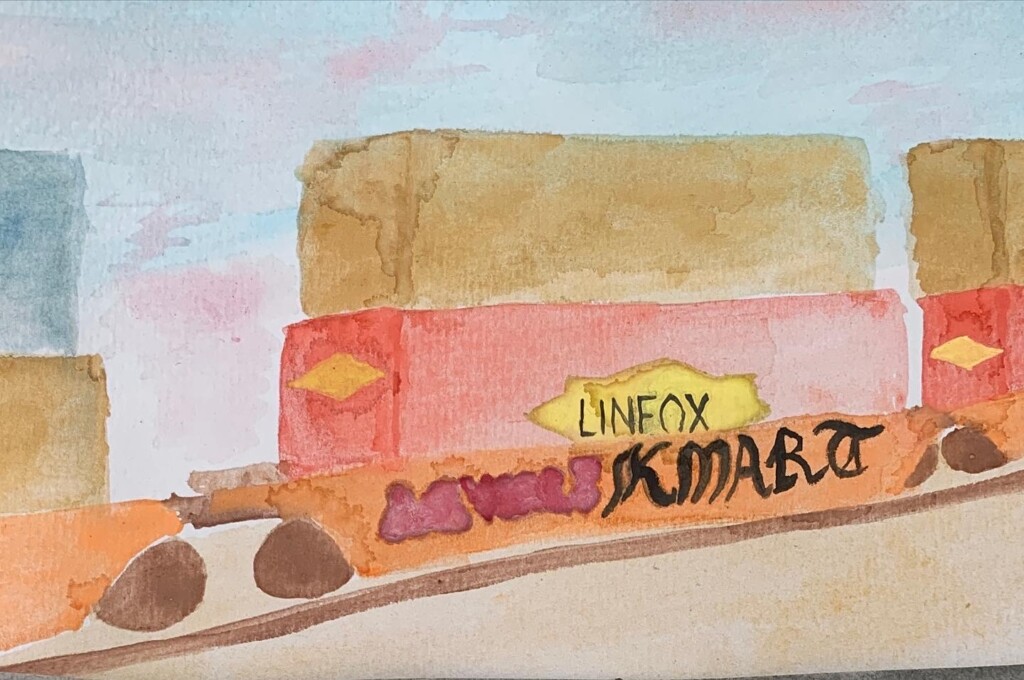

“La Durée” is a video study I made for ‘Cabinet’ group show at Mission to Seafarers (Narrm-Melbourne, 15 April 2023) exploring some of the themes I’m working on during this residency: freight trains and time travel.

During this online residency I’ll be documenting work continuing on the audio/literature project I started at my in situ residency at FAC in Dec 2022. Walyalup or Fremantle as a first site for it was apt, where I spent a lot of time around the port. A common thread in the work is ballast: the entity that fills ships’ hulls to keep them steady when not carrying cargo (the “ballast” here is just sea water itself), and the rocks under railway lines maintaining the tracks’ stability. It occurs in nature too: creatures like blowfish and argonaut octopi stay afloat thanks to water ballast in their bodies. So you go to this trouble to make something float, but then you have to weigh it down a bit for it to work properly – a kind of temperance.

Ballast is a vector for stowaways. Shipping ballast water is collected in coastal waters in one place then discharged in another, often full of organisms that get moved around from port to port. These creatures form a population of unwanted species when discharged in foreign environments, and have names like: Spiny Water Flea, North American Comb Jelly, Round Goby, Toxic Algae, Mitten Crab, Zebra Mussel, American Razor Clam, North Pacific Seastar. 3-5 billion tonnes of ballast water is transferred throughout the world each year, and the amount is increasing. Ballast water creatures are starting to turn up in new places as new shipping routes open up due to climate change, like the Northwest Passage in the Arctic Circle.

Rail freight (and its ballast) acts as a conduit for human stowaways, but its corridors also enable other species to mobilise in these relatively protected zones of industry. The history of trains is bound up in the history of time; time zones were created for them. Over the years I’ve wondered not just about the sentience hosted by trains, but their own imaginations and agendas. My favourite hobby is anthropomorphising stuff, but the iron horses make it pretty easy. I like to think all players have consciousness.